What is a Random Variable? (Draft)

Definition of a Random Variable

According to Gubner [1], Note 2.1, A function X from \(\Omega\) into \(\mathbb{R}\) is a random variable if and only if,

\[\{\omega \in \Omega : X(\omega) \in B\} \in \mathcal{A}, \; \forall B \in \mathcal{B}\]Here:

- \(\Omega\) : is the sample space.

- \(\omega\): outcome defined in the sample space.

- \(\mathcal{A}\): \(\sigma\)-algebra defined on subsets of sample space (\(\Omega\)).

- \(\mathcal{B}\): Borel \(\sigma\)-field is the smallest \(\sigma\)-algebra on \(\mathbb{R}\) containing all open subsets of \(\mathbb{R}\).

- \(B\): is the Borel set such that \(B \in \mathcal{B}\).

where:

- \(\{\omega \in \Omega : X(\omega) \in B \}\): is the preimage of the Borel set \(B\) under the random variable \(X\). It is a subset of \(\Omega\), representing the set of outcomes \(\omega\) that map to values in \(B\) under \(X\).

- \(\in \mathcal{A}\): This subset must belong to the \(\sigma\)-algebra \(\mathcal{A}\) i.e., the preimage of any Borel set \(B\) is an event that can be measured (assigned a probability).

If you understand the above definition in its entirety, then I congratulate you on your grasp of this fundamental concept of probability. If, on the other hand, you do not completely understand the above definition and struggle like me, then you are welcome to partake in this journey of understanding the nooks and crannies of “how a random variable is defined”.

Aim

The purpose of defining a random variable is to be able to study the probability associated with an experiment.

A random variable \(X\) is a function from the sample space \(S\) to \(\mathbb{R}\).

\[\begin{equation} X : S \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \end{equation}\]Sample Space, Outcomes and Events

When we run an experiment it could produce many possible outcomes. Set of all such possible outcomes is the sample space (\(\Omega\)) of the experiment. A subset of the sample space, which is a collection of possible outcomes is called an event.

Example

Consider an experiment involving ten successive coin tosses.

Experiment: Ten successive coin tosses.

Outcomes: Each outcome is a \(10\) character string with each character is either a H or T.

\[\begin{align*} \omega_1 &= \text{HHTTTHHTHH} \\ \omega_2 &= \text{HTHHTTTHHH} \end{align*}\]Sample Space: Set of all such outcomes is the sample space \(\Omega\)

\[\Omega = \{ \text{HHHHHHHHHH}, \text{HTHHTTTHHH}, \text{TTTTTTTTTT}, \cdots \}\]The total number of possible outcomes of the sample space is, \(\vert\Omega\vert = 2^{10} = 1024\).

Events: An event is a subset of the sample space.

Some examples are:

-

First Head Occurs on the 3rd Toss: The set of outcomes where the first Head appears on the 3rd toss:

\[E_1 = \{\omega \in \Omega : \omega = \text{TTHTTTTTTT or } \omega = \text{TTHHHHHHHH and so on.}\}\] -

Exactly 4 Heads in 10 Tosses: The set of outcomes with exactly 4 Heads: \(E_2 = \{\omega \in \Omega : \text{Number of H in } \omega = 4\}\)

Let’s re-define the definition of a random variable \(X\) in terms of the sample space and outcomes:

\[\begin{equation} X(\omega) : \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R} \end{equation}\]Here:

- \(\Omega\) represents the sample space, which is the set of all possible outcomes of the random experiment.

- \(\mathbb{R}\) is the set of real numbers.

- \(X(\omega)\) is a real-valued function that maps outcomes (\(\omega\)) to the real line (\(\mathbb{R}\)).

Probability Measure

The probability measure assigns probabilities to events (\(E\)), which is a subset of the sample space (\(E \subseteq \Omega\)).

Example

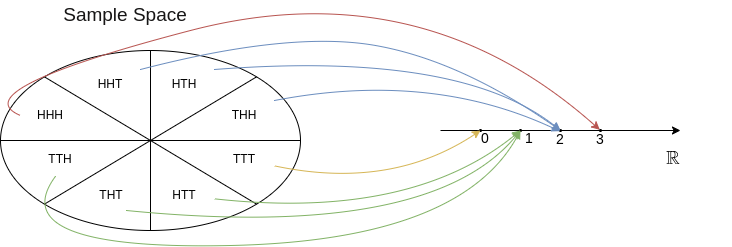

- Experiment: Toss a coin three times.

- Sample Space: \(\Omega = \{\text{HHH},\text{HHT},\text{HTH},\text{HTT},\text{THH},\text{THT},\text{TTH},\text{TTT}\}\)

-

Random Variable: Let \(X\) represent the number of heads:

\[\begin{align*} X(\text{HHH}) &= 3 \\ X(\text{HHT}) &= X(\text{HTH}) = X(\text{THH}) = 2 \\ X(\text{HTT}) &= X(\text{THT}) = X(\text{TTH}) = 1 \\ X(\text{TTT}) &= 0 \end{align*}\]

- Let the event be, “The number of heads is 2”, which would be represented by: \(\{\text{HHT}, \text{HTH}, \text{THH}\} \subseteq \Omega\)

- The probability of an event would be calculated by summing the probabilities of the outcomes in that event.

- As \(\{X=2\} = \{\text{HHT}, \text{HTH}, \text{THH}\}\), hence: \(P\{(X = 2)\} = P(\text{HHT}) + P(\text{HTH}) + P(\text{THH}) = \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{8} = \frac{3}{8}.\)

Hence, the random variable \(X\) creates a mapping from \(\Omega\) to \(\mathbb{R}\) and the probability law assigns probabilities to events such as \(\{X = x\}\), allowing us to compute the probability distribution of \(X\).

The sample space \(\Omega\), along with the collection of events \(E\) and the probability measure \(P\) defined on \(E\), form a probability space \((\Omega, E, P)\). The random variable \(X\) is a function that maps outcomes in \(\Omega\) to real numbers in \(\mathbb{R}\). It does so in a way to transfer the probability measure \(P\) from the events in \(E\) to \(\mathbb{R}\). This transferred probability measure on \(\mathbb{R}\) is called the probability distribution of \(X\). It tells us the probabilities of \(X\) taking on different values.

Purpose of this mapping

A random variable maps outcomes of an experiment into numbers. Why do we do this? Because it allows us to create a probability distribution. This distribution tells us how likely it is for the random variable to take on different numerical values. For example, if our random variable represents the number of heads in \(10\) coin tossess, the distribution tells us the probability of getting \(0\) heads, \(1\) head, \(2\) heads, so on and so forth. Instead of working directly with the messy details of ‘\(HHTHT_\cdots\)’ outcomes, we work with numbers and their associated probabilities.

Cardinality of a Set

The cardinality of a set refers to the size or number of elements in the set. Sets can have different cardinalities, which are broadly categorized as finite, countably infinite, and uncountably infinite.

-

A countably finite set is a set with a finite number of elements and can be put into a one-to-one correspondence with the first \(n\) positive integers, where \(n\) is finite.

- Example: The set \(A = \{2, 4, 6, 8\}\) has 4 elements that correspond to the natural numbers \(\{1, 2, 3, 4\}\).

-

A countably infinite set is a set with infinitely many elements, but these elements can still be put into a one-to-one correspondence with the set of natural numbers (\(\mathbb{N}\)).

- Examples:

- The set of all natural numbers: \(\mathbb{N} = \{1, 2, 3, 4, \dots\}\).

- The set of all integers: \(\mathbb{Z} = \{\dots, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, \dots\}\). - \(\mathbb{Z}\) can be mapped to \(\mathbb{N}\) using: \(f(n) = \begin{cases} 2n & \text{if } n > 0 \\ -2n + 1 & \text{if } n \leq 0 \end{cases}\)

- The set of even numbers, \(E = \{2, 4, 6, 8, \dots\}\) maps \(E \to \mathbb{N}\) with \(f(n) = 2n\).

- Examples:

-

A set is uncountably infinite if it contains infinitely many elements that cannot be put into a one-to-one correspondence with the set of natural numbers (\(\mathbb{N}\)). In other words, the set is too large to be enumerated, even in principle.

- Example: The interval \([0, 1] \subset \mathbb{R}\) is uncountably infinite. This can be proven by Cantor’s diagonal argument, which demonstrates that no list can include all real numbers.

Probability Distributions of a Random Variable

Once we define a random variable \(X\), we need a way to describe the likelihood of different values it can take. This is done through probability distributions.

A probability distribution specifies how the values of a random variable are distributed across the real line \(\mathbb{R}\), assigning probabilities to different outcomes in a way that satisfies the axioms of probability.

Why Do We Need Probability Distributions?

Consider an experiment, such as rolling a die or measuring the height of individuals in a population. The possible results of such an experiment are captured by the random variable \(X\). However, merely defining \(X\) is not enough—we need to quantify the likelihood of different outcomes. This is where probability distributions come in.

A probability distribution tells us:

- Which values of \(X\) are possible.

- How likely each possible value (or range of values) is to occur.

- How probabilities are assigned in a way that obeys the fundamental properties of probability.

Types of Probability Distributions

A probability distribution can be broadly classified into two types, depending on whether the range of the random variable is discrete or continuous:

- Discrete Probability Distributions: If \(X\) can take on only a finite or countably infinite set of values (e.g., \(0,1,2,3,\dots\)), then its probability distribution is described using a Probability Mass Function (PMF) and \(X\) is called a Discrete Random Variable.

- Continuous Probability Distributions: If \(X\) can take an uncountably infinite set of values (e.g., any real number within an interval on \(\mathbb{R}\)), then its probability distribution is described using a Probability Density Function (PDF) and \(X\) is called a Continuous Random Variable.

Examples

- Discrete Random Variable where range is countably finite:

- Experiment: Two successive rolls of a die.

- Random Variable: The sum of the two rolls is less than \(8\).

- Discrete Random Variable where range is countably infinite:

- Experiment: Roll a single six-sided die repeatedly where the sample space for each roll is \(\Omega={1,2,3,4,5,6}\).

- Random Variable: The roll count on which \(6\) appears for the first time.

- Continuous Random Variable where range is uncountably infinite:

- Experiment: Choosing a point \(a\) from the interval \([0,1]\).

- Random Variable: Associate the value \(a^2\) to such a point.

Despite these differences, both discrete and continuous distributions can be unified under the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF), which provides a cumulative measure of probability.

How We Define a Probability Distribution

To fully characterize a random variable, we define its probability distribution using the following three functions:

1. Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF)

The Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF), denoted by \(F_X(x)\), gives the probability that the random variable \(X\) takes on a value less than or equal to \(x\):

\[F_X(x) = P(X \leq x)\]This function applies to both discrete and continuous random variables and serves as the fundamental way of defining a probability distribution.

2. Probability Mass Function (PMF)

The Probability Mass Function (PMF), denoted by \(p_X(x)\), is used for discrete random variables. It provides the probability of each individual value:

\[p_X(x) = P(X = x), \quad \text{for all } x \in \mathbb{R}.\]The PMF satisfies the fundamental probability property:

\[\sum_{x} p_X(x) = 1.\]3. Probability Density Function (PDF)

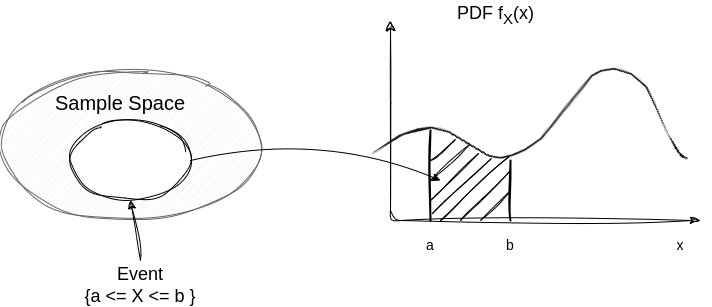

The Probability Density Function (PDF), denoted by \(f_X(x)\), is used for continuous random variables. Unlike the PMF, a PDF does not give probabilities directly but rather describes the density of probability across the real line:

\[P(a \leq X \leq b) = \int_a^b f_X(x) \, dx.\]The PDF must satisfy the property that the total probability over all possible values of \(X\) is 1:

\[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f_X(x) \, dx = 1.\]The Role of the Probability Distribution

A probability distribution is essential in probability theory and statistics because it allows us to:

- Compute probabilities for specific events.

- Determine expected values (mean) and variances, which summarize key characteristics of \(X\).

- Define statistical models for real-world applications.

- Understand relationships between different random variables.

Every real-world phenomenon that involves randomness—from stock market fluctuations to physical measurements—can be modeled using an appropriate probability distribution. The choice of the distribution depends on the nature of the experiment and the properties of the random variable.

Discrete Random Variable

Probability Mass Function

The probability mass function \(p_X(x)\) is defined as the probability of the event \(\{X = x\}\), which includes all outcomes in \(\Omega\) that result in \(X(\omega) = x\).

\[p_X(x) = P(\{X=x\})\]Here, \(x\) is any possible value of \(X\), the probability mass of \(x\), denoted \(p_X(x)\), is the probability of the event \(\{X = x\}\) consisting of all outcomes that give rise to a value of \(X\) equal to \(x\). The previous example defines the random variable and demonstrates an example of how a specific event (\(P\{X=2\}\)) is assigned probability value.

Q. What does it mean when we say: The random variable \(X\) has a binomial distribution?

If \(X\) is a binomial random variable with parameters \(n\) and \(p\). Then the PMF of \(X\) is defined as:

\[P(\{X=k\}) = \binom{n}{x}p^x(1-p)^{n-x}\]The above equation:

- Describes the probabilities of all possible values the random variable \(X\) can take.

- The event \(\{X=k\}\) is a subset of the sample space \(\Omega\) and contains all outcomes (\(\omega\)) for which \(X(\omega) = k\).

Continuous Random Variable

A continuous random variable can take an infinite number of possible values within a given range on the real line (\(\mathbb{R}\)).

For example, a random variable representing the height of people could be any real number within a plausible range (e.g., between 150 cm and 200 cm).

Cumulative Distribution Function

A continuous random variable is characterized by its cumulative distribution function (CDF). The CDF of a continuous random variable \(X\) is defined as:

\[F_X(x) = P(X \leq x) = P(\{\omega \in \Omega : X(\omega) \leq x\}).\]This function is crucial because:

- It provides a mapping from the sample space \(\Omega\) to real numbers.

- It allows us to define probabilities for intervals via the Borel \(\sigma\)-algebra.

Two Questions that naturally arise are:

- Ques: Why is a continuous random variables defined through a CDF but not something analogous to a PMF for a discrete random variable?

- Ques: What is a Borel-\(\sigma\) algebra?

- Ques: How is probabilities defined vis Borel \(\sigma\)-algebra?

Why CDF?

Similar to discrete random variables which are characterized by their PMF, a continuous random variable is described by a probability density function (PDF), denoted by \(f_{X}(x)\). The PDF gives the relative likelihood that the variable takes a particular value.

Unlike a probability mass function (PMF) for discrete random variables, the PDF is not the probability of a specific value. The probability that the random variable takes on a specific value is always zero for a continuous variable. Rather, the PDF is used to compute the probability that the random variable lies within a certain interval.

\[\mathcal{P}(a \leq X \leq b) = \int_{a}^{b} f_{X}(x) dx\]and can be interpreted as the area under the graph of the PDF.

Borel Field, and Borel Sets

In probability theory, the set of all real numbers, \(\mathbb{R}\), contains uncountably infinite elements, making it necessary to define a suitable collection of subsets for probability assignment. The most commonly used collection of subsets is the Borel \(\sigma\)-algebra, denoted as \(\mathcal{B}(\mathbb{R})\).

Definition: Borel \(\sigma\)-Algebra

The Borel \(\sigma\)-algebra is the smallest \(\sigma\)-algebra containing all open subsets of \(\mathbb{R}\). Formally, it is the smallest collection \(\mathcal{B}(\mathbb{R})\) such that:

- It contains all open intervals \((a, b)\), \([a, b]\), \((a, b]\), and \([a, b)\) for all \(a, b \in \mathbb{R}\).

- It is closed under countable unions, countable intersections, and complements.

A subset of \(\mathbb{R}\) that belongs to \(\mathcal{B}(\mathbb{R})\) is called a Borel set.

Defining a Continuous Random Variable via the \(\sigma\)-Algebra

A random variable is a function \(X: \Omega \to \mathbb{R}\) that satisfies the measurability condition:

\[X^{-1}(B) = \{\omega \in \Omega : X(\omega) \in B\} \in \mathcal{A}, \quad \forall B \in \mathcal{B}(\mathbb{R}).\]where:

- \(\Omega\) is the sample space.

- \(\mathcal{A}\) is the \(\sigma\)-algebra on \(\Omega\).

- \(B\) is a Borel set in \(\mathbb{R}\).

This means that every Borel set in \(\mathbb{R}\) must correspond to an event in \(\mathcal{A}\) on the sample space \(\Omega\). In other words, we construct probability measures on the real line by first ensuring that the random variable \(X\) is properly defined over the \(\sigma\)-algebra.

Example: Constructing a \(\sigma\)-Algebra for a Continuous Random Variable

Consider a continuous random variable \(X\) that represents the temperature in a city. Suppose the sample space is:

\[\Omega = \text{all possible weather conditions on a given day}.\]To model \(X\) as a random variable:

- Define \(\mathcal{A}\) as a \(\sigma\)-algebra on \(\Omega\) that includes all subsets needed to define probability.

- Ensure that the preimage of any Borel set \(B \in \mathcal{B}(\mathbb{R})\) is in \(\mathcal{A}\).

-

Define the probability measure \(P\) so that it assigns probabilities to temperature ranges, such as:

\[P(X \leq 30^\circ C) = P(\{\omega \in \Omega : X(\omega) \leq 30\}).\]

This construction ensures that all possible probability computations using \(X\) align with the probability space \((\mathbb{R}, \mathcal{B}(\mathbb{R}), P)\).

How the Normal CDF Maps to the Sample Space via Borel Sets

If \(X\) is a normal random variable with mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\), its CDF is given by:

\[F_X(x) = \int_{-\infty}^{x} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} e^{-\frac{(t-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}} dt.\]When we say “\(X\) follows a normal distribution,” we mean that:

- \(X\) is a measurable function from \(\Omega\) to \(\mathbb{R}\).

- The probability measure \(P\) is constructed so that \(X\) induces the normal CDF.

-

Every probability calculation corresponds to a Borel set:

\[P(a \leq X \leq b) = P(\{\omega \in \Omega : a \leq X(\omega) \leq b\}) = \int_{a}^{b} f_X(x) dx.\]

Thus, the normal distribution describes how probabilities are assigned to different Borel sets on the real line.

Connection Between PDF and Probability

For a continuous random variable \(X\), the probability that \(X\) falls within a specific interval is given by the area under the curve of its PDF:

\[P(a \leq X \leq b) = \int_{a}^{b} f_X(x) dx.\]This integral represents the total probability mass contained within the interval \([a, b]\). Since \(X\) is defined over a \(\sigma\)-algebra, this probability is assigned in a way that aligns with the measure \(P\).

Summary

- Infinite sets are structured via the Borel \(\sigma\)-algebra, which includes all open sets and is closed under countable operations.

- A continuous random variable is defined by ensuring that its preimages of Borel sets are measurable.

- The probability measure \(P\) on \(\mathbb{R}\) is induced by \(X\), making it possible to compute probabilities using the PDF and CDF.

- When we say “\(X\) has a normal CDF,” it means the induced probability measure aligns with the normal distribution, ensuring that every probability computation follows from the \(\sigma\)-algebraic structure.

This formalizes how continuous random variables fit within the rigorous mathematical framework of probability theory.

References

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

— Sir Isaac Newton

- Gubner, John A. Probability and Random Processes for Electrical and Computer Engineers. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Introduction to Probability, by Dimitri P. Bertsekas and John N. Tsitsiklis